People and places: Chrys Meader’s history of Marrickville

By Sue Castrique ©

It took several readings before I came to understand the significance of the cover of Marrickville: Rural Outpost to Inner City. The photograph shows Marrickville Town Hall being opened in 1922. On first glance the photo perfectly captures the book’s subject, but while the new town hall is imposing, within the ring of bunting and onlookers stands Winged Victory, her pedestal wreathed in garlands, her sword lifted to the air. This was the statue Chrys Meader tried so hard to save.

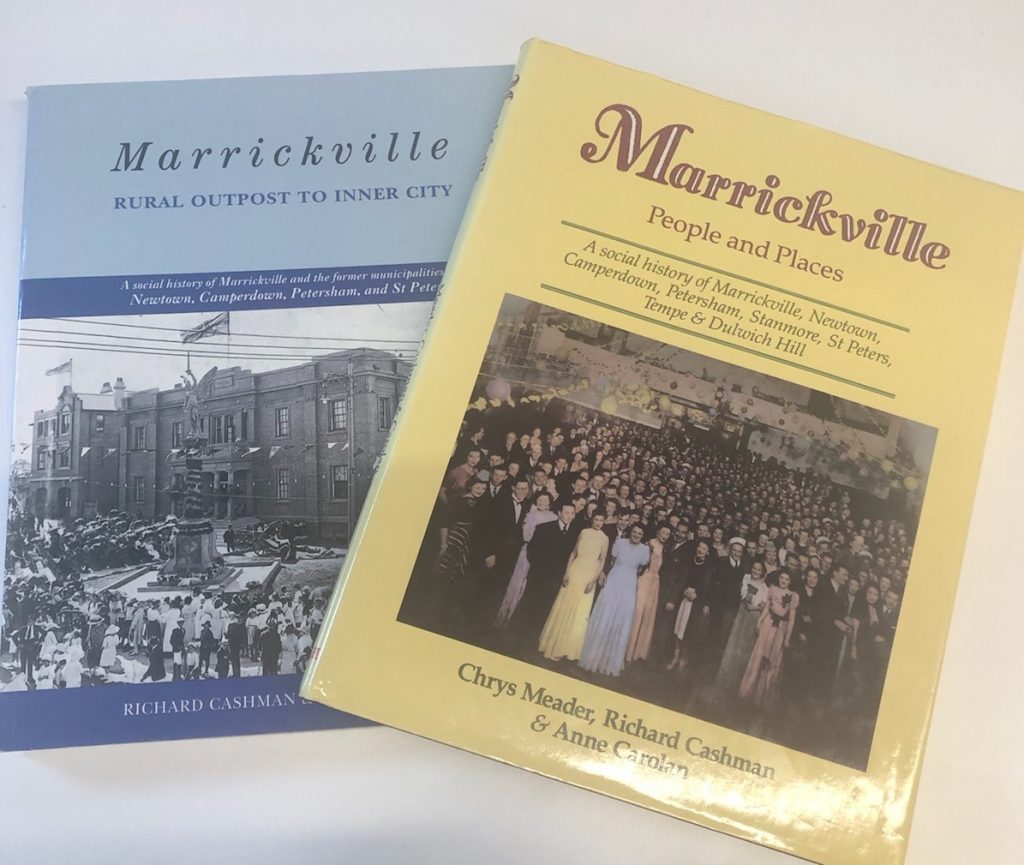

Chrys Meader and Richard Cashman wrote Marrickville: Rural Outpost to Inner City in 1990. Its companion Marrickville: People and Places was published four years later in 1994 with a third writer, Anne Carolan. Originally conceived as a single volume, they were split into two to make it easy for publication and readers. They have been essential local histories ever since.[1]

In significant ways Marrickville Council housed, defined and nurtured this history. Richard Cashman was a Marrickville councillor from 1980 to 1982 and Chry Meader a council librarian. They drew on an archive created over decades by Frances Charteris, the Chief Librarian at Marrickville Council from 1955. Frances had a keen historical consciousness and created the Local Studies Collection with community donations, records and photographs and the Archives Reference Collection from original council documents. Chrys continued to care for and add to the collections, retrieving valuable council documents from storage rooms, lofts and the ‘rat poison room’. Here was a gold mine of material bursting with all the small necessary details that are the backbone of historical research.[2]

There were not just printed documents. The library was a community hub for people and stories. As Diane McCarthy remembers, people dropped into the library to borrow books, but then stayed to talk, sharing memories and telling stories about where they lived and how they came to be here. This was a local history created from local archives and memory.[3]

Marrickville was defined in Cashman and Meader history by its political boundaries. They set their work within the local council of Marrickville which by 1990 had merged with the councils of Camperdown, Newtown, St Peters and Petersham, creating a sprawling local government area that stretched from Cooks River to Annandale.

As Chrys was aware, it was a place with a million local stories. The task was how to corral this expansive and unruly material between the covers of a book. Marrickville Council had produced a Jubilee history in 1911 and another in 1922 for the Daily Telegraph, both celebratory tales of civic progress and achievement. Cashman and Meader shifted the list of mayors and alderman to the appendix at the back and created a local history to answer new concerns.[4]

The two volumes were loosely structured. The first dealt with early colonial settlement and how large estates turned into suburbs. The second explored stories of local people then tracked the concrete markers of place in roads, bridges, schools, churches, parks, and pubs. The persistent theme was urbanisation and how the rural margins became the inner city. The picture of market gardens in Dulwich Hill on the back cover of Rural Outpost was a life now almost unimaginable.

Marrickville was changing in the late 1970’s and 1980s. As Cashman wrote, there was ‘the rediscovery of the inner-city, the decline of industry in the area, gentrification in some parts along, with an ever-changing migrant population – as some migrant groups moved in others moved out.’ Developers had also moved into Marrickville and were having an impact. Familiar landmarks might be gone overnight. The landscape of the past seemed to be quickly disappearing.[5]

The focus was on housing and heritage. Backed by new federal and state heritage legislation the Department of Environment and Planning funded a heritage survey in 1984 by Fox & Associates, the first comprehensive assessment of historical buildings in Marrickville. But Council was in turmoil over zoning and development. Councillors had been threatened and bashed, ALP branches were in disarray, even a librarian might find her car had been tampered with after a council meeting. Council was dismissed and Alex Trevallyan appointed as administrator.[6]

Outside of Council, community action groups were tackling issues like the third runway, pollution, and traffic management. Concerned that some Council aldermen and staff were unsympathetic to heritage, Peter Arnett, the Council’s Chief Town Planner suggested residents should form the Marrickville Heritage Society. It filled the gap left after the previous historical society folded in 1981. The new group galvanised support for the heritage plan and began to document the history of the area by starting a journal. Articles written by Meader, Cashman and Carolan and published in the journal became the first drafts of the book. With the adrenalin hit of Bicentennial funding in 1988, publication became possible.[7]

Out of the upheaval grew a belief that there was a distinct Marrickville identity that deserves our attention. Chrys had a long personal connection to Marrickville and its Council; it was part of her DNA. Her grandfather Oliver Meader worked in the Daley brick pit on Sydenham Road. Chrys and her father Charlie Meader were born in Marrickville and both worked for Marrickville Council. When Chrys’ mother died, Council generously supported the family by providing a house and the job of groundsman at Henson Park for her father who became Council’s longest serving employee.

I became acutely aware of those ties when I gave Chyrs a draft of my history of the Addison Road Community Centre, One Small World and asked for her feedback. She was generous with her comments but had one problem. In the 1950s both Fred Daley and Marrickville Council wanted to clear Marrickville of its ‘slums’ and convert the army site on Addison Road into housing. Chrys wanted the word ‘slum’ removed. I found that difficult because it was a word both Fred Daley and Council had used and which I was quoting. It also said something to me about Marrickville at that time. Chrys simply disagreed: Daley, she said, was wrong and I am sure she would have argued with him too.

Chrys was a fierce defender of Marrickville. She was not interested in historical labels or abstractions. She wrote within and for the local community, which meant work, family, church, the Labor Party and rugby league. Chrys’ method was empirical and profoundly humble, proceeding by the slow patient accumulation of detail: every street, every house might be known. The best example of Chrys’ writing is her entry on Sydenham for the Dictionary of Sydney. It is as if she was writing about well-loved neighbours: that ‘small community with a big heart’.[8]

The last two decades have seen a digital revolution that has changed historical research profoundly. Newspapers that were once held on microfilm in library basements and cranked forward one page at a time can now be searched instantly. Sands directories once on fiche are now in databases. For all its wonders, Chrys was acutely aware that few people understood the hard slog of research, the long hours needed before any of it might make sense. She worried that the work that went into the Marrickville volumes would not be appreciated.

But publication was only one of the host of projects Chrys Meader was involved with that expanded the historical consciousness of Marrickville. She assisted the Aboriginal History Project for MACC (Marrickville Aboriginal Consultative Committee) in 2006; spoke extensively about everything from Wardell’s murder to the influenza pandemic of 1919 and with characteristic fierceness argued against Winged Victory being removed from Marrickville to the Australian War Memorial: a struggle she ultimately lost. But Chrys was probably best known for her walking tours where she shined, bringing energy, enthusiasm and boundless knowledge.

The two-volume history of Marrickville in Rural Outpost and Brief Lives remain landmark historical works. They broke new ground in offering an expansive and systematic history, drawing together stories and sources into a single indispensable reference. They have been constantly relied on and referenced by heritage reports and conservation management plans about Marrickville ever since. There is no doubt they will be debated, argued with, and augmented by writers and researchers to come. But Meader, Cashman and Carolan made readers aware that the past is a powerful force that lives on and shapes the present. Their work helped create a sense of place and remains a compass point for Marrickville.

ENDNOTES

[1] R. Cashman & C. Meader, Marrickville, Rural Outpost to Inner City, Hale & Ironmonger, Alexandria, 1990. C. Meader, R. Cashman & A. Carolan, Marrickville, People and Places, Hale & Ironmonger, Sydney, 1994.

[2] C. Meader, ‘The world is made up of a million local histories’, Heritage: Journal of Marrickville Heritage Society, 6, 1990, pp46-9. R. Clement, ‘Marrickville Municipal Council: Archival Reference Centre: the first archivist’, Heritage, 5, 1989, pp46-8

[3] Diane McCarthy, Interview with Sue Castrique, 9 Dec 2022.

[4] 50th Anniversary of the Incorporation of the Municipality of Marrickville, 1861-1911, nd. Inner West Archives. Daily Telegraph, 10 Feb 1922, p4.

[5] R. Cashman, ‘A community heritage group: Marrickville’, in P. O’Farrell & L. McCarthy (eds), Community in Australia, UNSW, Sydney, 1991, p51.

[6] Fox & Associates, Marrickville heritage study, 1984. G. Richardson, Commonwealth of Australia, Senate, Hansard, 28 Feb 1984, pp59-64.

[7] Marrickville Heritage Society, Newsletter, vol 36, no 4, Jan 2020.

[8] C. Meader, Sydenham, Dictionary of Sydney, 2008, https://dictionaryofsydney.org/entry/sydenham]